-

Powering a New Era of High-Performance Space-Grade Xilinx FPGAs

Powering a New Era of High-Performance Space-Grade Xilinx FPGAs

Trademarks

UltraScale is a trademark of UltraScale.

All trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

1 Powering the XQRKU060: Key Challenges

As a result of its high performance, depending on its programmed capabilities (clock frequency, logic usage), the total on-chip power required for an FPGA could be as high as 30 W. The core voltage of the chip, VCCINT, needs a large percentage of this power. At about 0.95-V nominal (see the XQRKU060 data sheet and Xilinx Power Estimator [XPE] for exact values), depending on the bitstream deployed, this power could translate to more than 25 A of current. Additionally, because of the advanced XQRKU060 process-node technology, the VCCINT voltage electrical tolerance requirements are tight; this tolerance includes electrical performance as well as radiation effects. Therefore, powering up devices like the XQRKU060 requires a different approach to meet the tolerances for successful operation of the device. Let’s separate these challenges into DC and AC regulation.

2 DC Regulation

One obvious factor related to DC regulation is the DC setpoint accuracy of the converter supplying VCCINT. This DC accuracy depends on factors such as the accuracy of the converter’s internal reference, the passives used with the converter (such as feedback resistors) and the layout of the printed circuit board (such as ohmic drops). From these factors, the internal reference of the converter represents a large percentage of the voltage accuracy specified by the FPGA manufacturer. However, you should calculate the accuracy of the internal reference in a way that is representative of the application.

As an example, temperature heavily influences the voltage drift of a reference; thus, you should calculate the accuracy for the temperature range to which the devices will be exposed during the mission. Typically, this range is from –40°C to +90°C, which is smaller than the standard military temperature range of –55°C to +125°C used to characterize space-rated devices. The TPS7H4001-SP from Texas Instruments has an internal reference with ±1.5% accuracy across electrical and radiation conditions for the entire military temperature range. A simple calculation of the temperature coefficient (0.1 mV/°C) reveals that in the actual application (–40°C to +90°C), the accuracy of the internal reference is about ±1.1%. You must also take into account radiation effects that could potentially affect DC regulation.

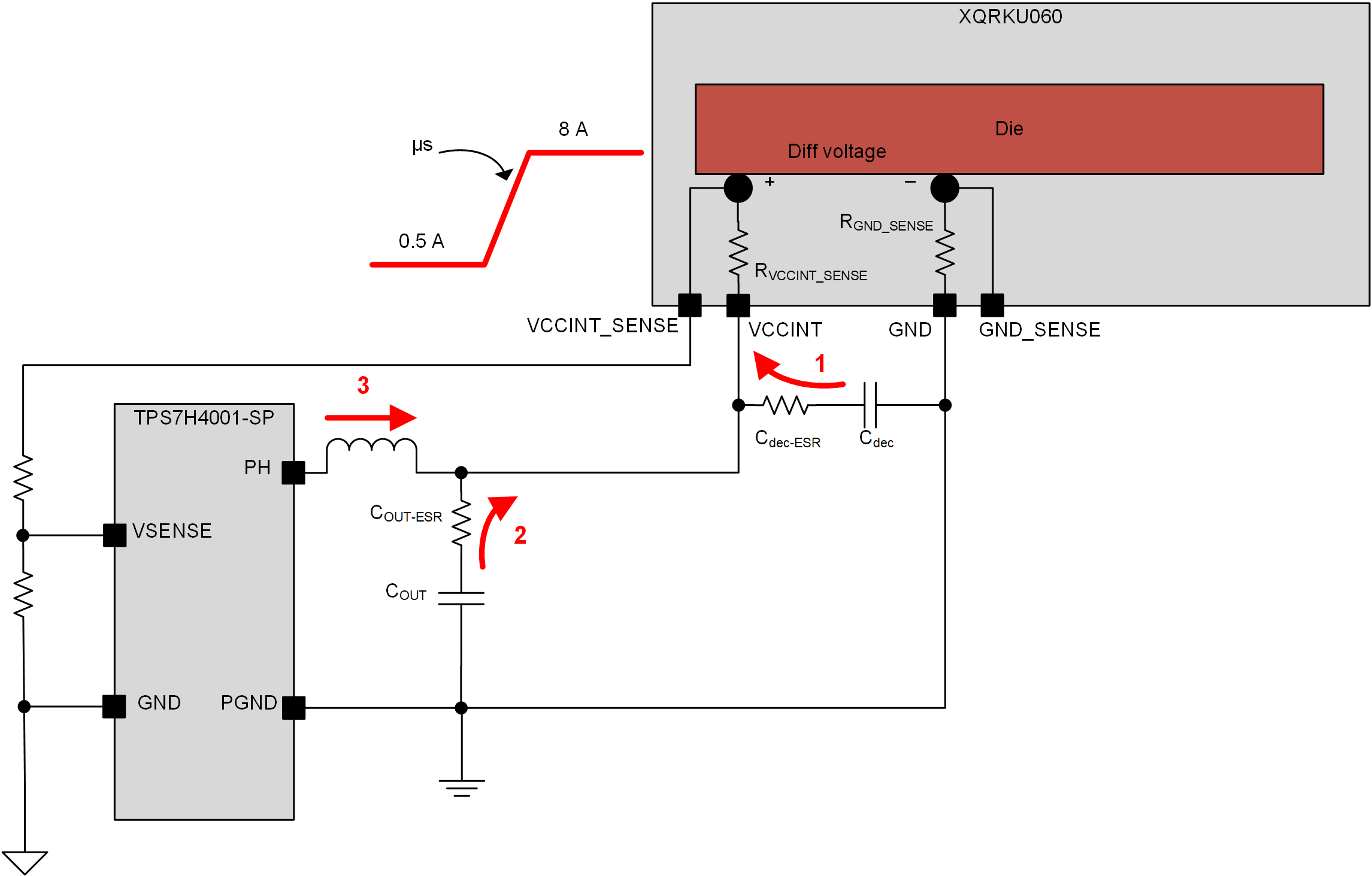

DC regulation typically refers only to the DC setpoint accuracy of the converter supplying VCCINT. The XQRKU060, as well as the converters that provide its power, is offered in a ceramic package because of its use in space applications. While ceramic packages offer hermeticity, they also present unique challenges not encountered in commercial-rated devices, including a larger footprint and larger resistance given the materials used in the package. In the case of the XQRKU060, the effect of ceramic package resistance in DC regulation is larger as the current increases, and the current will depend on the bitstream used. To mitigate this larger resistance, the XQRKU060 offers two pins, VCCINT_SENSE and GND_SENSE. Figure 2-1shows the connections needed between the TPS7H4001-SP and the XQRKU060 sensing pins, as well as a simple representation of the internal package resistance for VCCINT and GND.

Figure 2-1 XQRKU060 Sensing Connections

to the TPS7H4001-SP

Figure 2-1 XQRKU060 Sensing Connections

to the TPS7H4001-SPBecause the TPS7H4001-SP does not offer a GND sensing pin, using only the VCCINT_SENSE pin in the XQRKU060 for the feedback signal (VSENSE) compensates for the voltage drop created by the package resistance RVCCINT_SENSE, as shown in Figure 2-1. If you don’t use the GNDSENSE pin for regulation, there is a small resistance that you need to account for. XPE provides the exact value for VCCINT to account for this small resistance. If not used, you can route the GNDSENSE pin to an optional test point or leave it floating, as indicated in the XQRKU060 data sheet.

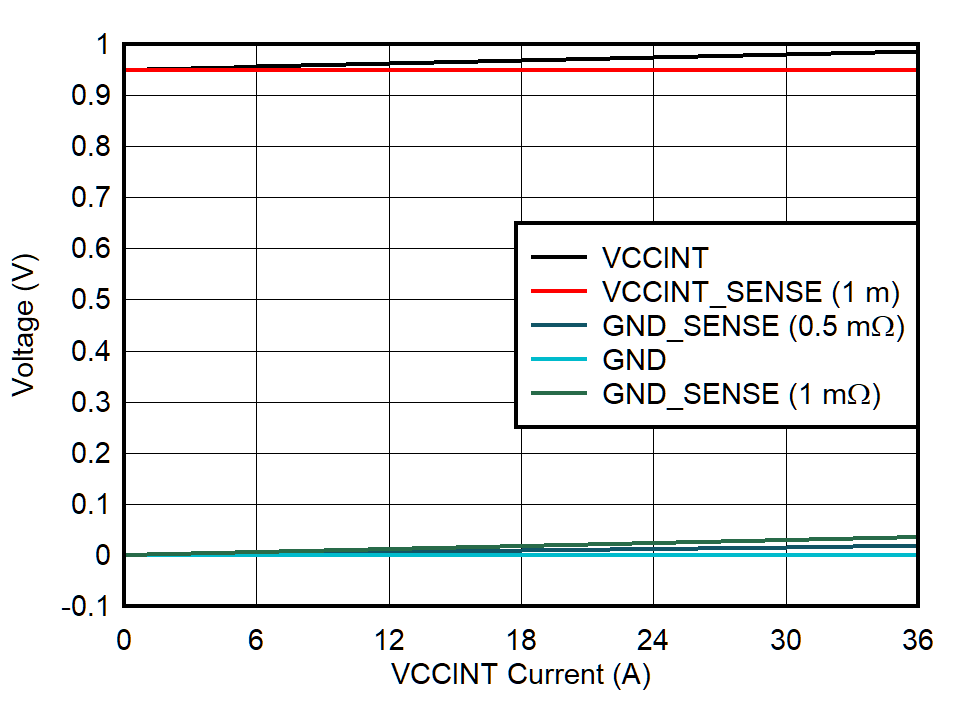

As the current supplied by the TPS7H4001-SP increases, the internal differential voltage across the XQRKU060 die might decrease, depending on the internal RGND_SENSE resistance. Figure 2-2 shows the relationship between VCCINT current and the different pin voltages for two different assumed values of internal package resistance. Both cases assume a nominal VCCINT voltage of 0.95 V.

Figure 2-2 Voltages at the XQRKU060 Pins

as a Result of Sensing Pins

Figure 2-2 Voltages at the XQRKU060 Pins

as a Result of Sensing PinsThe first scenario in Figure 2-2 assumes the same resistance value of 1 mΩ for both RVCCINT_SENSE and RGND_SENSE. In this case, you can see how the VCCINT_SENSE voltage remains constant at 0.95 V (dotted red line), while the GND_SENSE voltage (dotted black line) increases as the VCCINT current increases.

GND signals and planes are typically the least resistive in ceramic packages given the large number of pins and planes used. Therefore, Figure 2-2 also shows an example where RVCCINT_SENSE = 1 mΩ but RGND_SENSE = 0.5 mΩ. In this particular case, the increase in the GND_SENSE voltage (dotted blue line) as the VCCINT current increases is much less than when RGND_SENSE = 1 mΩ. It is important to reemphasize that when using XPE, even this low RGND_SENSE value is compensated in the exact VCCINT value indicated.

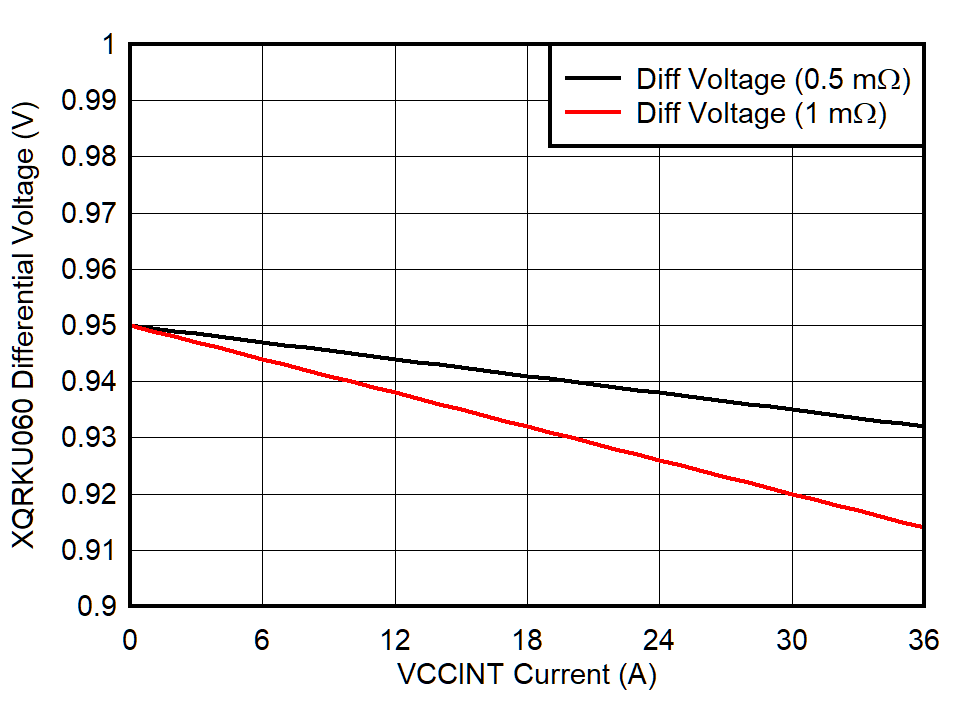

Figure 2-3 shows the impact of these two scenarios in the differential voltage across the XQRKU060 die. You can see that when RVCCINT_SENSE = RGND_SENSE = 1 mΩ, the differential voltage across the XQRKU060 die decreases to 0.914 V as the VCCINT current reaches 36 A. When RVCCINT_SENSE = 1 mΩ but RGND_SENSE = 0.5 mΩ, however, the differential voltage only decreases to 0.932 V as the VCCINT current reaches 36 A. While the 18-mV difference between these two scenarios might seem low, this translates to a 3.7% (VCCINTdiff = 0.914 V) vs. a 1.9% (VCCINTdiff = 0.932 V) DC-regulation tolerance (from 0.95-V nominal), which is significant in the context of VCCINT voltage tolerance requirements.

Figure 2-3 Differential Voltage Across

the XQRKU060 for Two Different RGND_SENSE Values

Figure 2-3 Differential Voltage Across

the XQRKU060 for Two Different RGND_SENSE Values3 AC Regulation

AC regulation is associated with load transients in the VCCINT rail. These load transients depend heavily on the programming code used in the FPGA. Consequently, we recommending writing the code in a way that avoids severe transients as much as possible – in other words, avoid enabling a large amount of logic in the FPGA at once. Load transients are always present, however, you need to properly address them to meet the regulation requirements.

Given the nature of some of these transients (some with high slew rates in the ampere-per-nanosecond range), the converter might not respond to the voltage drop caused by the transient quickly enough. This is where the decoupling capacitors recommended by Xilinx become critical (see the XQRKU060 data sheet for detailed information regarding decoupling capacitors for different transient scenarios). These decoupling capacitors are in addition to any internal decoupling capacitors typically included in FPGA packages. Figure 3-1 shows an example of an approximately 7-A load transient in the microseconds range.

Figure 3-1 AC Regulation Response Due to

Load Transients

Figure 3-1 AC Regulation Response Due to

Load TransientsInitially, the internal and external decoupling capacitors will respond to the current increase. The external decoupling capacitors are sized to match the worst-case expected transient based on the XQRKU060 data sheet recommendation and, as a result, they will handle the transient properly. In case the FPGA still requires additional current after the depletion of the decoupling capacitors, the output capacitors of the converter will supply current until the converter is able to respond. You must choose the crossover frequency of the converter and the respective feedback compensation accordingly for every application.

4 Radiation Effects

Along with DC and AC regulation, we recommend you consider any radiation effects introduced by the converter to meet the tolerance requirements from the XQRKU060. These radiation effects include total ionizing dose (TID) and single-event transients (SETs).

TID could introduce drift in the internal reference of the converter that could affect DC regulation. The TPS7H4001-SP is rated up to 100 krad(Si), and Texas Instruments tests every specification to meet the data sheet limits after exposure to 100 krad(Si). The internal reference of the TPS7H4001-SP shows very little sensitivity to TID, with a maximum drift of 2 mV (~0.3%) at 100 krad(Si).

Transients induced by heavy ions (SETs) are not as predictable as TID and could have a very negative effect on regulation. A converter sensitive to transients that shuts down the output of the converter or exceeds the maximum regulation requirements of the XQRKU060 could severely compromise the performance of the FPGA. Additionally, large and positive transients could potentially damage the FPGA.

The TPS7H4001-SP is fully characterized for SETs up to a linear energy transfer (LET) equal to 75 MeV-cm2/mg and shows resilient performance with a low number of SETs (<10 at PVIN = 5 V, VIN = 5 V) when the output voltage exceeds ±3% at a fluency of 10 million ions/cm2 (see the Single Events Effects Test Report of the TPS7H4001-SP for details). This translates to a very low SET cross-section of 2.18 × 10-7 cm2/device (PVIN = 5 V, VIN = 5 V). This SET performance, along with its TID rating of 100 krad(Si), makes the TPS7H4001-SP a reliable converter to power up the XQRKU060.